The Surrenders! Part I

How The Two Large Military Surrenders at Appomattox and Bennet Place Turned Into Victories — for Both Sides

No civil war in history had ever ended like this. In fact, no war had ever ended like this. As the surrendering Confederates marched up a dirt road to lay down their arms and flags, the victorious Union army, lining both sides of the road, saluted them. The rebels returned the salute. It was “honor answering honor,” wrote General Joshua Chamberlain, the hero of Gettysburg, and the Union general who ordered the unique tribute to his former enemies.

|

| Cannon at Appomattox battlefield and surrender site. |

So how did America’s bloodiest and most violent war come to such a sudden and honorable end? It’s easy to find out for yourself on a weekend trip by visiting the two surrender sites, which are only a few hours drive apart in Virginia and North Carolina. You can stand at the spot where both surrenders took place, stroll down country roads where little has changed since 1865, and — at a time when people are tearing down Civil War monuments and reinterpreting how we think about the Civil War – reach your own conclusions about the men who actually fought it.

As historian Shelby Foote said, “Any understanding of this nation has to be based on an understanding of the Civil War. It defined us.” And any understanding of the Civil War has to include an understanding of how these unusual surrenders came about and what they meant. Honor answering honor. There’s a concept worth a journey to explore.

The Road to Appomattox

At the end of March 1865, both Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant were worried. After three years of bloody warfare, Grant and the Union army had encircled Petersburg, the rail junction southwest of Richmond that protected the Confederate capital. But in a 10 month siege, Grant had racked up more than 40,000 casualties with very little to show for it. His great fear was that Lee and his 60,000 man army would somehow break out of the siege and head south to link up with Joe Johnson’s army of nearly 90,000 Confederates in North Carolina. Together, the Rebels could continue to fight for another year and a war weary Northern populace might not stand for that and sue for peace.

|

| Union trenches at Petersburg 1865 |

Lee, on the other hand, faced even greater challenges. His troops were starving, disillusioned, out of supplies and deserting. After 10 months of nearly constant trench fighting, moral was at its lowest point. And Lee knew his lines were spread too thin, and he could not continue to hold Petersburg.

And he didn’t. In a series of battles culminating at Five Forks, Grant pushed Lee out of Petersburg and forced him to retreat west across Virginia. Rather than just follow him, Grant was always sure to keep Union cavalry ahead of and to the south of Lee to prevent him from joining Johnson.

|

| The road that Lee took to his meeting with Grant in Appomattox Court House has changed little since 1865 |

By April 9, 1865, near the little village of Appomattox Court House, Lee realized his situation was hopeless. With his army surrounded and starving, Lee put on his best dress uniform (thinking that he would spend the evening as a prisoner of war), and told his generals, “There is nothing left me to do but go and see General Grant and I would rather die a thousand deaths.” After sending a white flag with a note to Grant, he sat down under an apple tree to await Grant’s reply.

This is the place to join him. Rather than start at the main visitor center, the best way to enjoy Appomattox Court House National Historic Park is to start about a mile to the west, at a roadside stop on Hwy. 24 called “The Apple Tree Site.” Because a rumor started that Lee actually surrendered here under an apple tree, the entire orchard was cut down by soldiers looking for souvenirs. So there are no historic witness apple trees here today, but you can still sit where Lee sat by the Appomattox River in a quiet place that is otherwise unchanged and think, as Lee must have done sitting in his fine uniform, how it all came down to this.

|

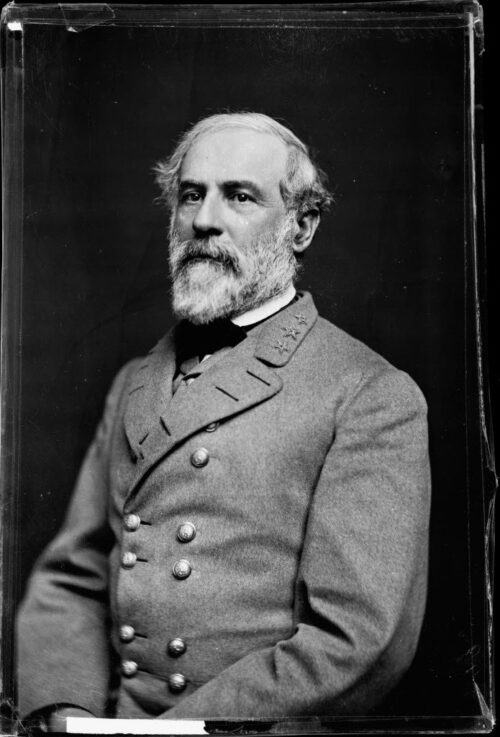

| Robert E. Lee |

The son of a Revolutionary War hero, Lee had been the second best student in his class at West Point and had fought with bravery in the War with Mexico. At the start of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln offered Lee full command of all Union armies. Although a slave owner (like 12 of America’s first 18 presidents) Lee abhorred the idea and wrote, “Slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil.” But he could not draw his sword against his family and friends in Virginia, so when the state succeeded, he went with them. As he sat under the apple tree, he knew that in a cruel irony, the U.S. government had seized his house in Arlington, VA, and turned his front yard into a cemetery for the war dead. All 400,000 graves in Arlington National Cemetery today are on land once owned by Robert E. Lee that the U.S. government took from him.

With Lee in the Apple Orchard

It’s difficult to imagine Lee’s thoughts. Around him, the South was in ruins. A quarter of the men of military age in the South were dead, and nearly every city, factory and railroad was destroyed or under occupation.

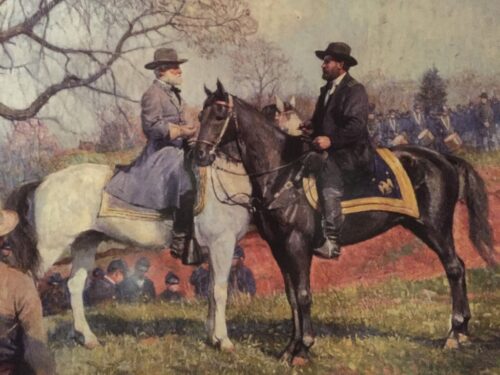

When he finally received a note from Grant asking him to find a location for a meeting, Lee climbed aboard his famous gray horse Traveler and with just one aide with a white flag, rode down the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road toward the Union lines.

|

| The road Lee took to the McClean House is unchanged and looks much like it did in 1865. |

You can follow Lee down this same road through a landscape that is virtually unchanged. The road is lined with a split-rail fence with views of rolling farm land. Birds sing and it is deadly quiet out here in the country. In about a mile, a village of 20 buildings comes into view. Ten are original from the 1860s or earlier; another ten have been painstakingly reconstructed to what they would have looked in 1865.

|

| The reconstructed McClean House in Appomattox |

All cars are parked some distance away, so you are literally seeing the town of Appomattox Court House just as Lee would have seen it. There’s a tavern and stores, some farmhouses and even the county jail. In the center of town is the impressive Court House with its bell tower. As you walk along the dirt and gravel roads, costumed interpreters will greet you. When I asked one where the bookstore was, he looked puzzled and said, “Ain’t got no bookstore in town, but there’s a general store over yonder.” They don’t break character.

It was here that Lee met local resident Wilber McLean and was ushered to his house. McClean had lived near the first battle of the Civil War in Manassas, VA. He moved to get his business away from the fighting, so it was with great irony that the war ended in his parlor.

|

| The Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road climbs a small hill to where Grant entered the scene. |

Instead of going into the house, continue on the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road for another half mile up a small hill, with fences and views of the countryside in all directions. At the top is a cemetery of 18 graves, each with a Confederate flag. These were the Southern boys who had the hard luck of being the last killed in the last action on the last two days of the war on the eastern front. It was at this spot that Ulysses S. Grant rode up and met General Phil Sheridan and was informed that Lee was waiting for him in a house down below.

|

| A small graveyard for the last Southern soldiers killed in battle. |

With Grant on Stage Road

An extremely modest man, Grant was, as usual, wearing the uniform of a private with the bars of a Lieutenant General sewn on the shoulders. He was muddy, from a long ride, and he never wore a sword.

You can now turn around and re-approach the village from the direction Grant would have come. If anything, this approach is even more beautiful and timeless today as you descend a small hill, the road a dirt ribbon lined with fences as it curves to a small village of white buildings below.

The short walk gives you time to consider the position and feelings of Grant. He too had gone to West Point and fought with bravery in the War with Mexico, but from there on, his life differed greatly from that of Lee. Depressed by serving away from his family, Grant took to drinking and was forced to resign from the army. He failed at every business he entered and became so poor that he was the only US president who lived with his family in a log cabin that he built with his own hands. By the time the war started, Grant was reduced to working as a clerk in his father’s leather business.

|

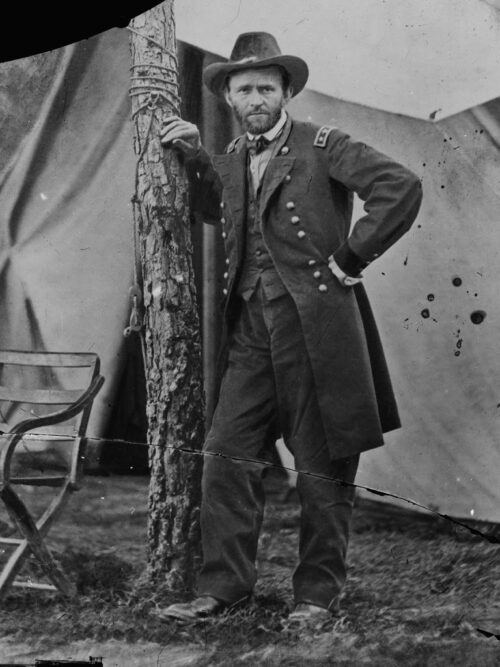

| U.S. Grant |

But Grant had gone to West Point and with the war starting, officers were needed. Grant was given some basic military jobs drilling raw recruits. Through a political friendship, he secured a small independent command and quickly demonstrated a military brilliance that has had few equals in history. As he rode down the hill, Grant had many contemporary critics who considered him a “butcher” who won victories only by having superior numbers. But today, modern historians consider Grant one of the greatest military geniuses of all time with his victories at Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and here at Appomattox all masterpieces of military strategy.

As he approached the McClean House, Grant tied his horse Cincinnati next to Lee’s Traveler and the two most famous horses in America, well known to every citizen at the time, chewed grass together, peacefully, side by side.

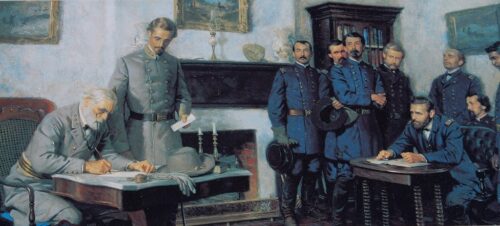

Inside, Grant was embarrassed by his shabby and muddy uniform and his first act was to apologize to the splendidly dressed Lee. They reminisced about Mexico and then got down to business. Grant had conferred with Lincoln, and together they wanted nothing but that the Southern armies would lay down their arms, return to their homes and obey the laws of the country. Grant added that all Southern officers would be able to keep their side arms, a great military honor at the time. Lee said this would have a “very happy effect upon my army.”

|

| The McClean House in 1865. The original was torn down by speculators in 1893 hoping to make money from it. It was rebuilt in 1940s. |

Lee then mentioned that in the Confederate army, the soldiers owned their own horses, unlike the U.S. where they were owned by the army. Grant, having been a small farmer, knew the value of a horse in the spring to putting in crops, and allowed the Confederates to take their horses with them. Again, Lee said, this will have “the best possible effect upon the men.” Lee also stated that his men were starving, and Grant immediately ordered rations sent to the Confederate camps. The papers were drawn up and signed. The two generals went outside, Lee mounted, and they saluted each other.

When Lee returned, he was surrounded by his troops, many crying, begging him to break the army up into small guerilla bands and continue the war. But Lee asked them to accept the parole, return to their homes, and obey all local laws. He later wrote, “I believe it to be the duty of every one to unite in the restoration of the country and the reestablishment of peace and harmony.”

On Grant’s side, the victorious Union army began celebrating and firing off victory cannons, but when Grant heard it, he ordered an immediate stop. He told his officers, “The war is over, the rebels are our countrymen again, and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field.” He later wrote he was “sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought.”

Over the next few days, some 30,000 parole forms were printed and given to the Southern troops, and in small groups of three to four, they set off walking on the long trudge home to Texas, Alabama, Mississippi and all points south. Soldiers from the north and south mingled together and shared food and stories. Even Lee was able to joke, when he saw his old army friend George Meade, who commanded the Union army at Gettysburg. Lee said, “What are you doing with all that gray in your beard?” Meade smiled and replied, “You have to answer for most of it.”

It looked for one brief, shining moment that a war as violent as the Civil War, fought over an issue as divisive as slavery, could actually end in a peaceful way. And then, on April 14, 1865, just five days after the surrender, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. And everything changed.

IF YOU GO: The modern town of Appomattox moved several miles from the surrender site at the old village of Appomattox Court House, so while today the modern town has chain hotels, restaurants and all services, the National Park site is virtually unchanged from 1865.

|

| The Lee Chapel in Lexington, VA where he is buried |

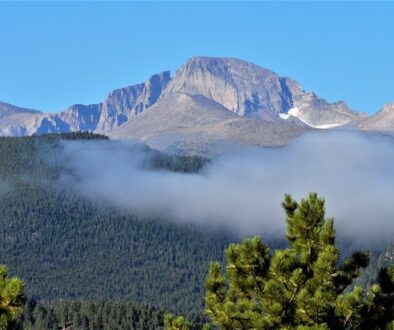

There are plenty of places to stay and eat in Appomattox, but better is to travel an hour more west to Lexington, VA, where Robert E. Lee is buried. Lexington is the home of the Virginia Military Institute (where Stonewall Jackson taught before the war) and Washington and Lee University, of which Lee was president after the war. They are both buried here, Lee in a beautiful chapel on the campus, Stonewall in a small graveyard on the edge of town.

Even the horse Traveler is buried here, in a tomb beside Lee, just outside the church. Lexington is one of the prettiest towns in Virginia, a peaceful, historic place, surrounded by gorgeous homes, all on the edge of the Shenandoah Mountains.

There are many memorials to Lee in town, but it is well to remember, that Lee himself was against any type of monument to the war. He wrote in 1869 about a proposed Gettysburg monument, “I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife.”

|

| Lee most likely would have disapproved of the many statues in his honor and thought it best to forget the war and move on. |

Tourist information: Lexington:

The Surrenders, Part II (coming soon)

|

| Bennett Place, North Carolina where Joe Johnson surrender to William Techcumsa Sherman. |

Most people, mistakenly, think that Appomattox is where the Civil War ended. In truth, there were still 90,000 well-supplied Confederate soldiers ready to do battle, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis was ordering them to fight. It was the second surrender, now preserved as a North Carolina state park, where Joseph E. Johnson surrendered to William Techcumsa Sherman at Bennett Place, that has often been forgotten and overshadowed – but might actually be the more significant of the two major surrenders. That’s because something dreadful and game-changing happened between the two surrenders. President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.