The Surrenders, Part II

How America’s Two Largest Surrenders in the Civil War Turned Out to be Victories – For Both Sides.

To read: Part I:

Part II

Shortly after 10 p.m., on April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth walked up the back stairs of the Ford Theatre in Washington D.C. and entered the private box overlooking the stage. There was no guard. As an actor, Booth knew the play being performed, a comedy from England called “Our American Cousin.” There was a particular line in act three, scene two, that always drew laughter. Thinking the laughter would conceal the sound of a shot, Booth waited for the line, then as the audience howled, he walked up, placed a .44 single shot derringer pistol behind the head of President Abraham Lincoln, and squeezed the trigger, changing all history.

|

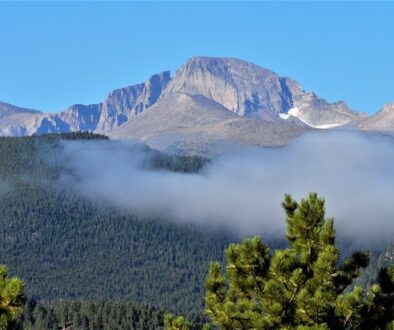

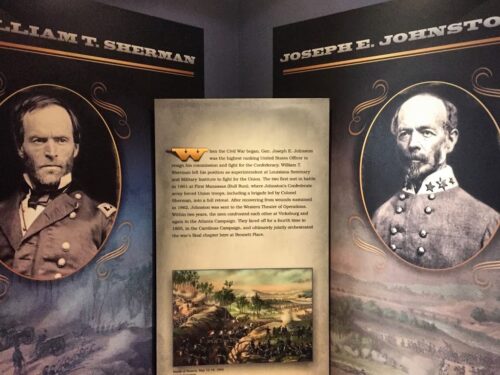

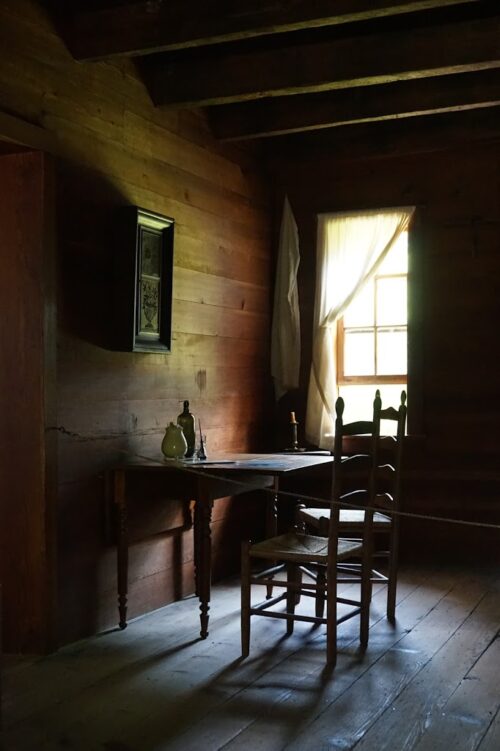

| Bennett Place where the largest surrender in American history took place looks unchanged from April 1865. |

We’ll never know, of course, what would have happened had Lincoln lived, but it’s easy to see the immediate effect his death had on the great Civil War and the surrender of the remaining Confederate armies. It caused havoc.

You can visit the site where this second, post-assassination surrender (the largest surrender in American history) happened at Bennett PlaceState Historic Site, Durham, North Carolina, and relive the tense few days where the end of the Civil War hung in the balance. It’s a quiet place today, re-creating exactly what the homestead looked like in 1865. But the story told in the museum here is quite suspenseful. But for the thoughtful and brave actions of a few men, the American Civil War might have broken up into guerilla warfare and, like other civil wars, lasted for decades.

|

| Bennett Place near Chapel Hill, North Carolina |

Most people mistakenly think the Civil War ended on April 9, 1865, when Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. But there were, in fact, still 90,000 armed Confederate troops in the field and Confederate President Jefferson Davis wanted them to keep fighting.

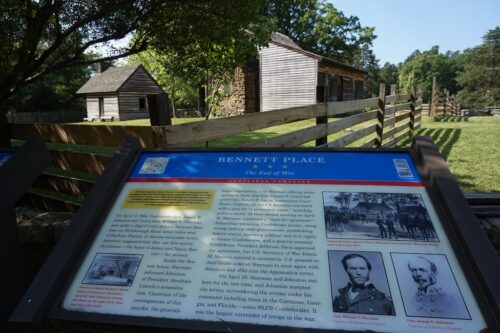

The Confederate commander, General Joseph E. Johnson, did not. Johnson had been a classmate of Robert E. Lee at West Point and had fought with distinction in the Mexican and Seminole wars. He was against both slavery and secession, but as a Virginian, he felt honor bound to fight for the South. However, Johnson disagreed greatly with President Davis on strategy. Davis wanted the South to hold territory and aggressively attack the Union army.

|

| An exhibit in the museum at Bennett Place |

Johnson, realizing the South had much fewer resources, wanted to follow the strategy George Washington had used against the British in the revolution – that is to avoid pitched battles, retreat when necessary, and outlast the enemy.

By the end of the war, Johnson’s military career had been mixed. He had won some battles, lost many others and had been relieved of command several times, both by wounds and by presidential orders. But in 1865 with the South in ruins and facing its final crisis, Davis had no one else to turn to, and he re-appointed Johnson to command the last great Confederate army.

|

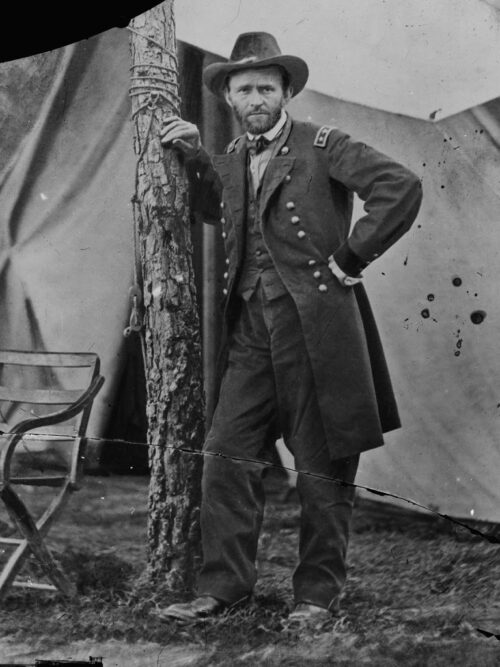

| William Tecumseh Sherman |

Facing Johnson was his old adversary, William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman had fought and defeated Johnson in the battles leading up to Atlanta, and had become, after Grant, the most famous and well known general in the Union Army. Once accused by the press of being insane, the volatile red-haired Sherman had recovered public esteem and won brilliant victories at Atlanta and on his March to the Sea campaign. His main strategy – eliminate the South’s ability to wage war by destroying their farms, railroads and factories – is often credited with ultimately winning the war, but also credited as the first “total war” waged by armies on civilians in modern times.

By April 1865, both Sherman and Johnson realized the war was over and they both wanted peace. To continue it, Johnson wrote, would be “murder.” Johnson asked for a truce and it was agreed the two generals would meet on April 15. However, on his way to the meeting, Sherman got one of the biggest shocks of his life. A coded telegram arrived stating that not only had Lincoln been assassinated, but Secretary of State William Henry Seward had also been attacked by an assassin with a knife, and though Seward lived, in the hysteria surrounding Washington, it was believed there would be further assassination attempts made on Grant’s life, and even on Sherman’s.

|

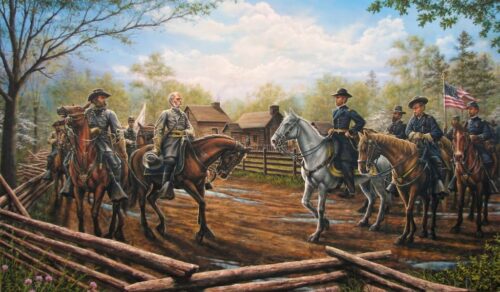

| Johnson and Sherman meet on the Hillsboro Road, with the Bennett House in the background. By artist Dan Nance |

Fearing what his troops would do when they heard the news, Sherman swore the telegraph operator to secrecy. He then continued under a flag of truce to meet Johnson on the Hillsboro Road. After introductions on horseback, Sherman asked, “Is there somewhere private we can talk?” Johnson said he had just passed a small farmhouse. And thus an obscure frame farmhouse belonging to James and Nancy Bennett was to become one of the most important sites in American history.

|

| Bennett Place today is a walk back in time to an 1865 homestead |

The original cabin burned down, but today, a home from the same era that looks just like it was placed on the foundation. The chimney is original. The surrounding Bennett Place park, like Appomattox, puts cars way off to one side so that once you enter the historic area, you can get the maximum time capsule effect of going back to a different era. There are a dozen structures and barns lining the original country dirt road. It’s difficult to imagine the shock of the Bennett family in this remote rural area when Generals Sherman and Johnson tied up their horses, knocked on the farmhouse door and asked if they could use their house for a few minutes.

|

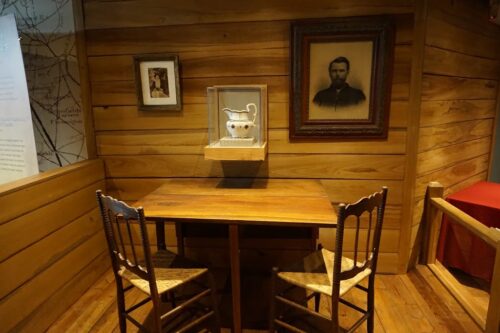

| A reproduction of how the table was set up for their meeting in Bennett’s house. |

As soon as the two generals were alone, Sherman handed Johnson the telegram. He wrote later, “I showed him the dispatch announcing Mr. Lincoln’s assassination, and watched him closely. The perspiration came out in large drops on his forehead, and he did not attempt to conceal his distress.”

Realizing now the importance of ending the war immediately before the north took vengeance for Lincoln’s death, Johnson proposed that rather than just surrendering his 90,000 men, what if he could surrender all Confederate forces throughout the South? It would be a brilliant stroke ending all potential fighting at once. Sherman and Johnson agreed to go back to their commanders with the proposal and meet at Bennett Place the following day.

There, on April 16, after hours of discussion back and forth, they hammered out surrender terms, which they both signed. An interesting anecdote was that Johnson brought along John C. Breckenridge, a former U.S. Vice President and now a Confederate Major General. Breckenridge was a lawyer and it was thought he could help with the language.

At the start of the meeting, Sherman went to his saddlebags, brought out a bottle of whiskey, and allowed everyone to pour a large glass. He put the bottle back in the saddlebags.

At some point in the meeting, Sherman, heavily distracted and without thinking, went over to the saddlebags, poured himself another large glass of whiskey, and put the bottle back without offering any to the Confederates. Breckenridge, a Kentuckian, never forgot that and later told Johnson. “General Sherman is a hog. Yes, sir, a hog. Did you see him take that drink by himself? No Kentucky gentleman would ever have taken away that bottle.”

|

| The table and chairs from the meeting in the museum. The milk jug was on the table during the meeting. |

Meanwhile, in Washington, there was total chaos with Lincoln’s funeral, unimaginable grief, a new president and fear of future assassinations. But that was nothing compared to the reaction when Sherman’s surrender terms finally made it to Washington. Back in March 1865, Sherman and Grant had met with Lincoln to discuss surrender terms, and Lincoln had told both his generals that he wanted to go easy on the Confederates and unite the country and his only concern for a military surrender was that the rebel troops lay down their arms, go home and obey the laws of the United States.

Sherman either didn’t understand this, or was bamboozled by the Confederate officers in his haste to end the war. But at any rate, his surrender terms went far beyond military matters and offered pardons to all Confederates, government and military, and allowed the soldiers to take their weapons back to arsenals in their own states. In the vengeful attitude that had seized Washington after Lincoln’s assassination, this was tantamount to treason. The surrender terms were rejected, Sherman was blasted as a traitor (or a fool) in the press, and Grant was ordered to go to Raleigh, take control of the army and force the Confederates to accept the same terms as Lee, or the truce would end and the war would start again in 48 hours.

|

| A cannon that was silenced, but would go to war again if Davis had his way. |

Two courageous things happened that saved the country from future bloodshed. One took place because of the great friendship that existed between Grant and Sherman. Rather than embarrass his friend, Grant charted a private boat and train and traveled to Sherman in secrecy. In Raleigh, Grant explained the situation, and left it up to Sherman to handle. No one in either army at the time ever knew that Grant was there. He came and left in secrecy and by doing so, saved Sherman’s career and reputation.

When Sherman told Johnson the surrender terms had been rejected, Johnson conferred with Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Davis exploded. He ordered Johnson to send him all the cavalry troops and to break the infantry up into small bands that could fight on their own, or later be brought back together as an army. The war was to continue.

|

| Grant traveled secretly to Raleigh to save his friend Sherman’s reputation and command. |

It was here that the second courageous act happened. Joe Johnson blatantly disobeyed his orders and on his own authority surrendered his forces under the same terms given to General Lee. The final, third meeting of Johnson and Sherman and this last surrender also took place in the Bennett farmhouse. The war, for all practical purposes, was over.

Strangely, Johnson and Sherman, who had never met before Bennett farm, became good friends and remained so for life. When Sherman died on Feb. 4, 1891, Johnson traveled north to be an honorary pallbearer. It was a cold rainy day and Johnson was repeatedly begged to put on a hat or go inside, but he said of Sherman, “If the positions were reversed, he would not do so.”

Joe Johnson died one month later from pneumonia that he caught at the funeral of his friend.

IF YOU GO:

One of the great things about visiting Bennett Place is that you can stay nearby in Chapel Hill, one of the most beautiful college towns of America. Home to the University of North Carolina, the downtown is a long main street lined with bars, breweries, bookstores (with cats napping in the window), coffee shops, church steeples, restaurants and grand spreading shade trees that lead off into a picture book campus of lawns and historic buildings.

Somethings not to miss:

|

| The Carolina Inn |

Carolina Inn. Located on the campus, the 185-room inn dates back to 1924 and offers the ultimate in Southern hospitality in a gorgeous setting. Afternoon tea is served 2:30-4:30, Thursday-Sunday, or stop by their outdoor patio for a cocktail after strolling through the pretty, tree-shaded campus.

|

| Chapel Hill has eight breweries |

Top of the Hill Restaurant,Brewery, Distillery North Carolina’s growing reputation for craft beer is exemplified here with outdoor rooftop decks, great food, and a very attractive bar. There are eight breweries and countless bars in Chapel Hill, but this is the one not to miss.

Silent Sam. Erected in 1913, this statue of a Confederate soldier faces Franklin Street from the UNC campus, and has been controversial almost from the start. It was put up either as a memorial to dead Confederate soldiers, or as monument to white supremacy, depending on who you talk to. Campus legend says that if a virgin walks by, he’ll shoot off his rifle…thus he is “Silent Sam.”

|

| Silent Sam on the University of North Carolina campus |

Following the riots and violence over a plan to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, VA, there were demonstrations in front of Silent Sam also calling for its removal. By state law, it would take an act of the North Carolina Legislature to remove a historic monument, and no bill has yet been introduced.

Carrboro: This funky, quirky, artsy little town is where the railroad came to Chapel Hill. It’s more of a neighborhood then a separate community, being only about a 10-15 minute walk from the campus along Franklin Street to Main Street. It’s an entertaining walk of bars, restaurants, the Carr Mill Mall (built in an 1898 cotton mill) and the famous Cat’s Cradle nightclub, known for 40 years of live music. The town’s motto is: “Feel free.” Enough said.

|

| The Ayr Mount Historic Site in Hillsborough has 256 acres of grounds, including the beautiful Poet’s Walk |

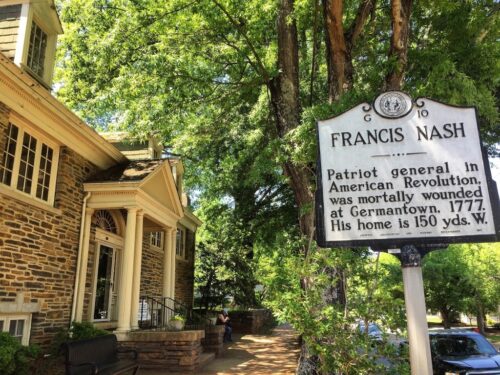

HistoricHillsborough: This is a charming small town America type of place that looks almost New Englandish, which is appropriate since it dates back to the American Revolution. The downtown backstreets are lined with wonderful historic homes and gardens.

|

| The historic back streets of Hillsborough go back to the Revolution |

The town is justly proud of its River Park, which has paths following the scenic Eno River, as well as a reconstructed Occaneechi Indian Village, showing native life from the 17th century. Nearby, the Ayr Mount Historic Site is the big attraction for the area with a sprawling 265 acres of grounds surrounding a powerful 1815 Federal-style plantation home.

Johnston County: Interstates 40 and 90 intersect in Johnston County, making it an important stop for people crossing the state in any direction. Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site is here, marking the last full-scale action of the Civil War on March 19-21, 1865. Once you get off the main highways, Johnston County is deep North Carolina, filled with great food, drink and Southern hospitality.

|

| Jeremy Norris at Broadslab Distillery |

Broadslab Distillery has a fun tour where owner Jeremy Norris will pour you samples of their authentic “moonshine,” which is a distilled corn whiskey made the same way four generations of his family have made it – many of them illegally in the days of prohibition or late at night under the moon to avoid paying taxes.

The Redneck BBQ Lab in Benson offers pulled pork, brisket, turkey, ribs, chicken, green beans, collards and cornbread, all prepared by members of the Redneck Scientific competition BBQ team. Why is it called a lab? Visit it and find out, but go hungry.

Johnston County has a “Beer, Wine & Shine Trail” that will guide you to deep South breweries, moonshine distilleries and wineries.

Very fun is Hinnant Family Vineyards, which has a series of wines honoring the most famous local daughter of the region, Ava Gardner.

|

| Ava’s Allure |

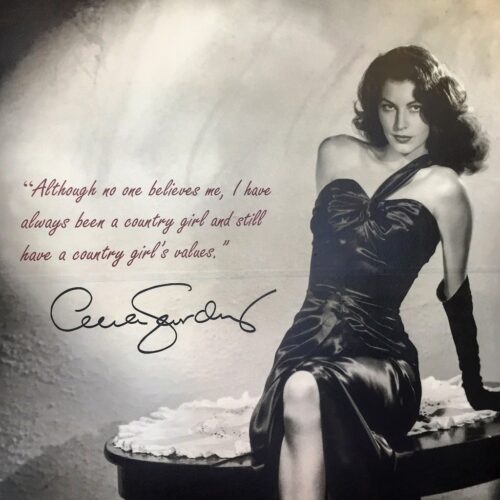

There’s also a museum devoted to Ava in Smithfield that is definitely worth a visit. Ava Gardner grew up in this area, and although she was one of the most glamourous of Hollywood stars and lived for years in Spain and London, she chose to be buried back here close to the place of her childhood in nearby Sunset Memorial Park.

The museum has costumes, photos and mementos from her amazing 50-year career, which included three marriages: to one of Hollywood’s biggest stars, Mickey Rooney; to one of the big band swing era’s most famous musicians, Artie Shaw; and to one of the world’s most famous crooners, Frank Sinatra. But she always maintained she was a North Carolina country girl at heart.

|

| Go hungry to the Redneck BBQ Lab in Johnson County, home to incredible food, craft beer and distilled spirits. |

|

| You might find yourself surrendering the charms of Ava Gardner at the Ava Gardner Museum in Springfield. |